When Noam Chomsky challenged himself to write a sentence that was grammatically correct but made no sense at all, he came up with “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.” Chomsky overlooked the human drive to make sense out of everything, even nonsense. There is poetry in his sentence, and, after a vertiginous moment of disorientation, we move rapidly from crisis to the discovery of meaning, with truths often more profound than what we find in sentences that make complete sense. There is magic in nonsense, for words turn into wands and begin to build new worlds—Wonderland, Neverland, Oz, and Narnia. Presto! We are in the realm of counterfactuals that enable us to imagine “What if?”

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

“Important—unimportant—unimportant—important,” those are the words of the King as he tries to figure out which of the two “sounds best.” There he sits in a court of law, with the jury box upside down and “quite as much use one way or the other,” telling us that beauty trumps sense. When I was ten years old, I fell in love with Alice in Wonderland, in part because my stern, white-haired teacher told me that it was a book for adults not children, in part because it was there that I first learned about the wonders of disorientation.

“Important—unimportant—unimportant—important,” those are the words of the King as he tries to figure out which of the two “sounds best.” There he sits in a court of law, with the jury box upside down and “quite as much use one way or the other,” telling us that beauty trumps sense. When I was ten years old, I fell in love with Alice in Wonderland, in part because my stern, white-haired teacher told me that it was a book for adults not children, in part because it was there that I first learned about the wonders of disorientation.

Brothers Grimm, “The Juniper Tree”

When my children were young I read them a fairy tale called “The Juniper Tree.” I reached the part when the boy is decapitated by his stepmother—she slams the lid of a chest down on his head. I started editing and improvising like mad, especially when I saw what was coming: making a stew from the boy’s body parts for his dad’s supper. Fairy tales and child sacrifice? Cognitive dissonance quickly set in, and that’s what put me on the road to studying what Bruno Bettelheim famously called the “uses of enchantment.”

When my children were young I read them a fairy tale called “The Juniper Tree.” I reached the part when the boy is decapitated by his stepmother—she slams the lid of a chest down on his head. I started editing and improvising like mad, especially when I saw what was coming: making a stew from the boy’s body parts for his dad’s supper. Fairy tales and child sacrifice? Cognitive dissonance quickly set in, and that’s what put me on the road to studying what Bruno Bettelheim famously called the “uses of enchantment.”

Hans Christian Andersen, “The Emperor’s New Clothes”

Almost everyone loves this story about a naked monarch and a child who speaks truth to power. What I loved about the story as a child was the mystery of the magnificent fabric woven by the two swindlers—light as spider webs. It may be invisible but it is created by masters in the art of pantomime and artifice, men who put on a great show of weaving and making fabulous designs with threads of gold. They manage to make something out of nothing, and, as we watch them, there is a moment of heady delight in seeing something, even when nothing but words on a page are before us.

Almost everyone loves this story about a naked monarch and a child who speaks truth to power. What I loved about the story as a child was the mystery of the magnificent fabric woven by the two swindlers—light as spider webs. It may be invisible but it is created by masters in the art of pantomime and artifice, men who put on a great show of weaving and making fabulous designs with threads of gold. They manage to make something out of nothing, and, as we watch them, there is a moment of heady delight in seeing something, even when nothing but words on a page are before us.

Henry James, “The Turn of the Screw”

What got me hooked on books? I remember a cozy nook where I retreated as a child into the sweet serenity of books only to be shocked and startled in ways I thankfully never was in real life. What in the world happened to little Miles in that uncanny story about a governess and her two charges? There had to be away to end my profound sense of mystification. It took some time for me to figure out that disorientation and dislocation was the aim of every good story. Keats called it negative capability, the capacity to remain in “uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts.”

What got me hooked on books? I remember a cozy nook where I retreated as a child into the sweet serenity of books only to be shocked and startled in ways I thankfully never was in real life. What in the world happened to little Miles in that uncanny story about a governess and her two charges? There had to be away to end my profound sense of mystification. It took some time for me to figure out that disorientation and dislocation was the aim of every good story. Keats called it negative capability, the capacity to remain in “uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts.”

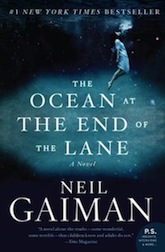

Neil Gaiman, The Ocean at the End of the Lane

“I make things up and write them down,” Gaiman tells us. In this long short story, we travel with the narrator into mythical terrain. It dawns on us only ever so gradually that a path with briars and brambles can be a time machine drawing us back to a childhood. In a place charged with what Bronislaw Malinowski called a high coefficient of weirdness, we meet mysterious cats, along with a magna mater in triplicate, and also discover the healing power of recovered memories.

“I make things up and write them down,” Gaiman tells us. In this long short story, we travel with the narrator into mythical terrain. It dawns on us only ever so gradually that a path with briars and brambles can be a time machine drawing us back to a childhood. In a place charged with what Bronislaw Malinowski called a high coefficient of weirdness, we meet mysterious cats, along with a magna mater in triplicate, and also discover the healing power of recovered memories.

Originally published in February 2015.

Maria Tatar chairs the program in folklore and mythology at Harvard. She is the author of many acclaimed books on folklore and fairy tales, as well as the editor and translator of The Turnip Princess, The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, The Classic Fairy Tales: A Norton Critical Edition, and The Grimm Reader. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Maria Tatar chairs the program in folklore and mythology at Harvard. She is the author of many acclaimed books on folklore and fairy tales, as well as the editor and translator of The Turnip Princess, The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, The Classic Fairy Tales: A Norton Critical Edition, and The Grimm Reader. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

How do you leave out Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons?

“a magna mater in triplicate” — not. The three generations of the Hempstock women represent the Great Goddess in her three aspects: Crone (Granny), mother (Ginny), and maiden (Lettie)

@1, Stein wasn’t writing nonsense she was writing agonizingly literary high style that was meant to impress not delight.

As you probably can guess I have a deep dislike for Gertrude Stein’s work.

I have for some time considered “The Emperor’s New Clothes” social satire, where HCA makes fun of the flock mentality of people to like what the majority like, and pretend to be smarter than they really are. But of course such satire would not be well recieved by the target audience of the time when the same audience was the target of the satire. So the social satire is hidden inside a fairy tale. The fairy tale begins where the little boy makes all the other people realize that the Emperor is naked and start laughing. In a more realistic story the little boy would have been stoutly ignored and people would have kept admiring the non-existent New Clothes.

Also, I think the satire is as apt today as it was then, if not more.

@2, respectfully, I think that’s another way of saying she was writing nonsense.

@@.-@, perfectly apt, until recently. Say, within the last two years :-)

One thing about “Alice in Wonderland” is that some of the nonsense is making fun of specific things, and some of it is just nonsense. I recommend reading “The Annotated Alice”, because it’s interesting to be able to understand the jokes – some of the random rhymes are parodies of things any child at the time would have known.

See Seanan McGuire’s “Wayward Children” series for some fascinating and amusing categorizations of “nonsense” and “logic” fantasy worlds.

I can’t help feeling that everything by David Wong belongs in this category.

James Thurber’s fairy tales, particularly The Thirteen Clocks:

“the only Golux in the world and not a mere device”

“a prince whose name begins with X and doesn’t”

“something I have hold of has no head!”

“You’ll never live to wed his niece. You’ll only die to feed his geese. Goodbye, goodnight, and sorry.”

“I can feel a thing I cannot touch and touch a thing I cannot feel. The first is sad and sorry, the second is your heart.”

“Remember laughter. You’ll need it even in the blessed isles of Ever After.”

… okay, so it’s a book that once you start quoting, it’s hard to stop.

Rootabaga Stories.

John Bellairs’ first novel, The Pedant and the Shuffly, is a prime example of nonsense. It was collected in the anthology Magic Mirrors a few years back, along with an unfinished sequel to The Face in the Frost.

Jeff Noon has borrowed (and written a sequel to) Alice In Wonderland, so he’s a good candidate, but there’s also Jasper Fforde, who’s books’ definitely sail close to Carrol’s whimsical nonsense.